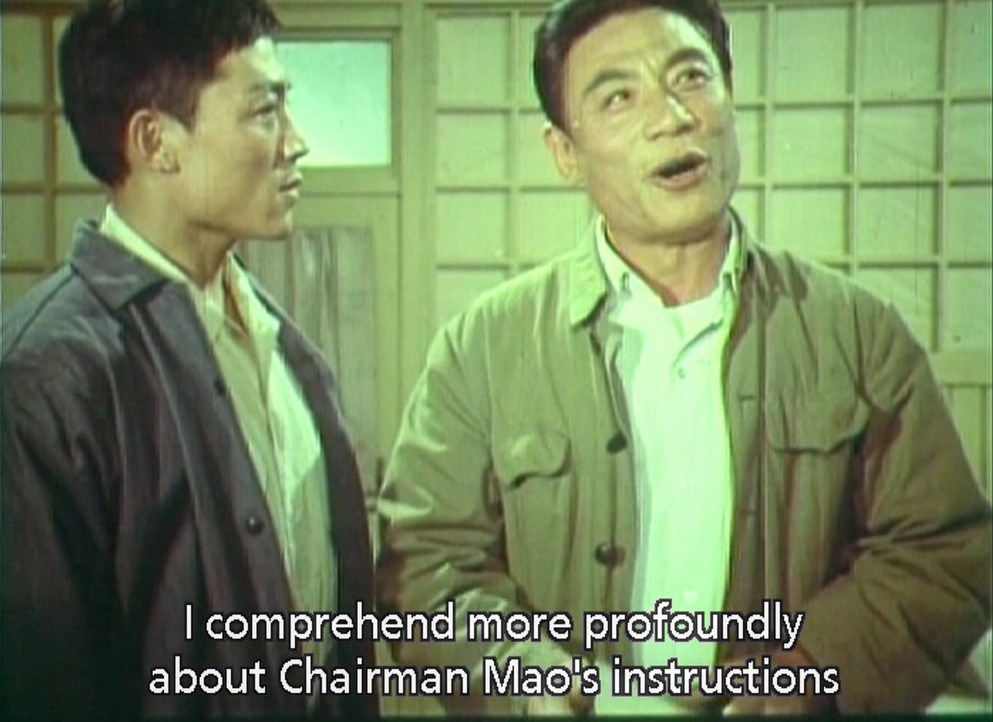

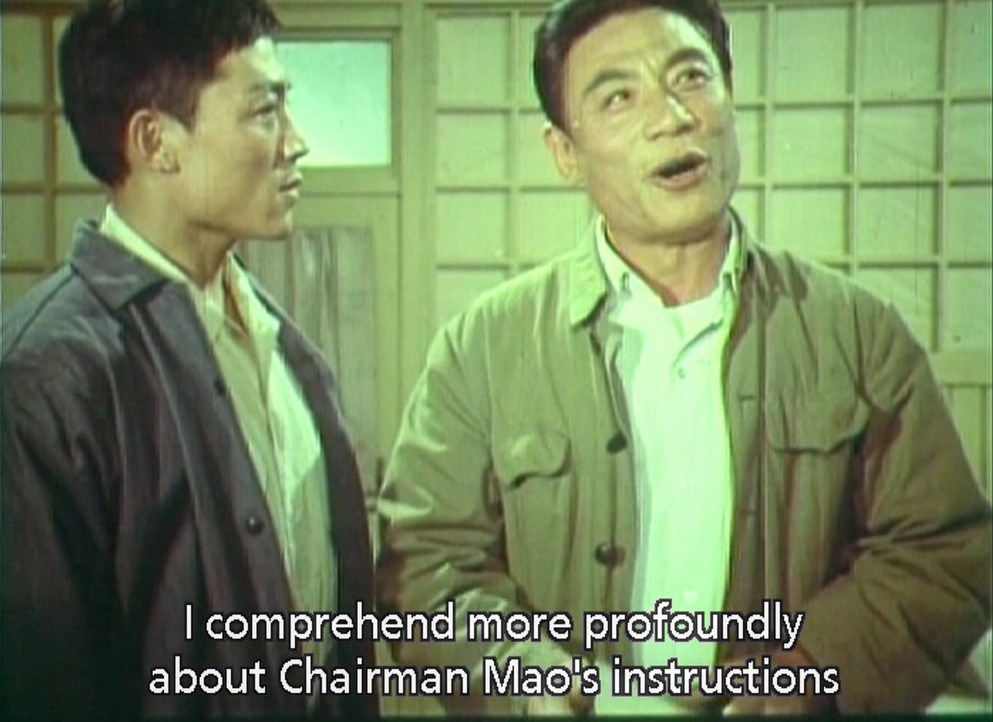

Breaking With Old Ideas

China

During the period of China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76), feature film production all but ceased, with only 12 feature films made (Zhang & Xiao 1998, 101). A booklet titled “Four Hundred Films to be Criticised” was circulated and many professionals from the already decimated film industry were criticised and tortured. One of those films was director Li Wenhua’s Breaking with Old Ideas (Juelie), released in 1976. While Mao Zedong declared the Cultural Revolution complete in 1969, its policies remained active until the death of his military adviser Lin Biao in 1971, and in place until his death in 1976. Among those was the “Down to the Countryside” movement, in which youth were transported from cities to rural areas to perform agricultural labour and be rinsed of bourgeois ideology. Breaking with Old Ideas depicts an earlier period, with the action taking place between 1958 and 1961, however it is similarly concerned with philosophies of education. Rosalind Delmar and Mark Nash (1976, 74) summarise the question at the heart of the film as: ‘What sort of educational institutions and methods are most suited to the needs of the peasants?”

Breaking with Old Ideas responds to this question in a rather upbeat way, combining entertainment and didacticism in a text closely aligned with Communist Party of China positions. The former peasant Long Guozheng arrives to a mountainous rural village in which he has been appointed by the government as Principal of the local agricultural college. Invariably exhibiting a positive spirit, Long is at odds with the Vice-Principal and Dean who desire that their college might emulate city universities. In one scene, a large crowd of local students are denied the opportunity to take an entrance exam over institutional concerns about academic standards. Long on the other hand is a staunch proponent of education available freely for all, and that such education should combine practice with theory; the new building must be built in the mountains in closer proximity to the peasants and their farms. He thus echoes Mao, who stated “Education must serve proletarian politics and be combined with productive labor” (in Johnson 1978, 44). Long and his supporters are visually contrasted with the principal villains through make-up and lighting, and portrayed in larger profile. The stark opposition conventional of melodrama means for William Johnson that Breaking with Old Ideas “‘solves’ a social or political issue in terms of personalities” (1978, 46). With everyone focused on this revolution in educational priorities, most notably in the complete absence of love interests or sexual desire, Breaking with Old Ideas provides a rather idealist picture of agricultural labour, in which everyone “enjoys perfect health” and “Productivity, industrialization, communization, family life, the status of women and countless other issues simply do not exist” as local concerns (Johnson 1978, 46). – Liam Grealy

Further reading:

– Delmar, R. and Nash, M. (1976). Breaking with old ideas: Recent Chinese films. Screen. 17(4): 67-84.

– Johnson, W. (1978). Reviewed work(s): Breaking with old ideas by Li Wen-hua. Film Quarterly. 31(3): 42-48.

– Zhang, Y. & Xiao, Z. (1998). Encyclopedia of Chinese film. London & New York: Routledge.