Crazed Fruit and Yūjirō Ishihara

Japan

Crazed Fruit is one of the five taiyōzoku (sun-tribe) films released in 1956, premiering on 12 July and following Season of the Sun on 17 May and Punishment Room on 28 June. 1957 was the year in which the sale of cinema tickets peaked in Japan, from which point television emerged as a serious alternative. Like Season of the Sun and Punishment Room, Crazed Fruit is also based on a novella by Shintarō Ishihara, the young man awarded the Akutagawa Prize for Season of the Sun. Crazed Fruit is probably the best known of the taiyōzoku films, remembered not only for its story but the directorial form taken by Kō Nakahira. The combination of creative framing, camera techniques, and edits employed by Nakahira across the seventeen day shoot situated him as a forerunner of the Japanese new wave, despite being a contract director for Nikkatsu with only one previous directorial credit, in Beef Shop Frankie (1956). Nakahira later left Japan for Hong Kong, where he changed his name to Yang Su Hsi and remade Crazed Fruit as Summer Heat in 1968.

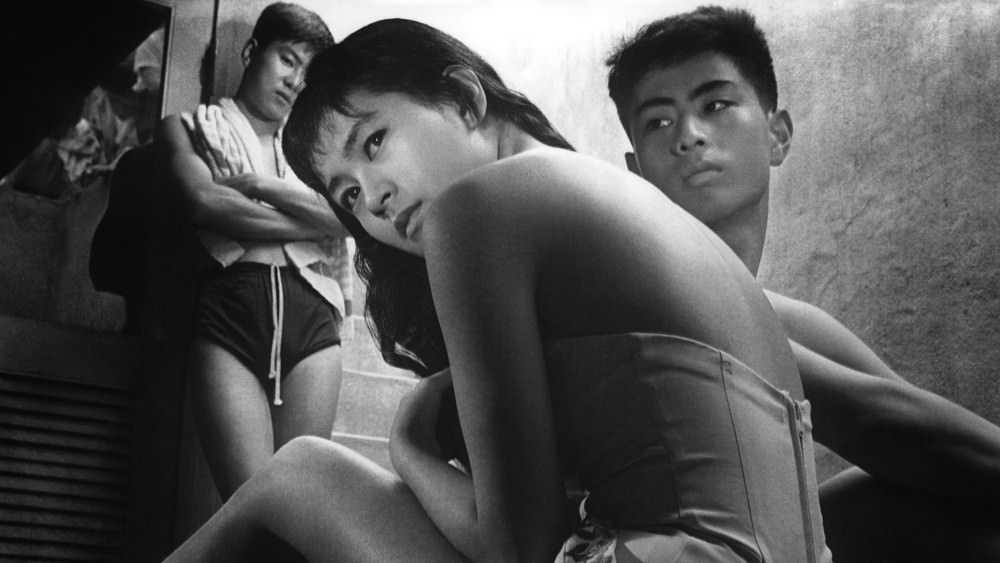

Crazed Fruit centres on a love triangle between two college-age brothers, Natsuhisa (Yūjirō Ishihara) and Haruji (Masahiko Tsugawa), and the object of their affections, Eri (Mie Kitahara) (Yūjirō and Kitahara married in 1959). The setting and drama is typical of the taiyōzoku films, with a group of young men engaging in hedonistic and at times delinquent pursuits, from sailing, to dancing, drinking and brawling, at the beach, amusement park, jazz club, and parent-free villas. The naïve Haruji is the younger of the brothers, and becomes taken with Eri when they come across her in the water during a sailing trip. A romance develops, and the jealous Natsuhisa deduces that Eri is already in a relationship – with an older American businessman – which he exploits to begin his own sexual relationship with her. A morbid conclusion sees the younger brother remain alive while Natsuhisa and Eri are killed in a boating “accident”.

Yūjirō Ishihara was the younger brother of the original novella’s author, Shintarō, and his casting imported the connotations of their taiyōzoku lifestyle and their real-life wealthy family. Cynical, competitive, sexually-driven, and self-consciously styled, Yūjirō differed from Japan’s post-war male movie stars. “Long hair doesn’t go with Hawaiian shirts”, he proclaims, in an expression that signals the youth’s ambivalent appropriation of American popular culture; later on, Yūjirō’s friend Frank (Masumi Okada) is mistaken in a bar for a foreigner and responds “Got any shochu?”, signaling the drink’s Japanese and working-class connotations. Yūjirō shifted his persona in later film, music, and television projects, adopting a softer guise across a career that situates him as one of Japan’s best known all-time performers and certainly Nikkatsu’s “biggest star. . . starring in around 90 popular youth-oriented action or musical films for the studio” (Sharp 2011, 101). But in Crazed Fruit, Michael Raine (2005) suggests that the masculinity evident in Yūjirō’s performance “models the looks, diction, and attitudes for which Shintaro had become famous.” The taiyōzoku films establish positions from which young female characters actively desire sexual encounters, and where male bodies are on show, even while male relations are strongly homosocial (Standish 2005). Regarding the former U.S. Occupation, Raine (2006) suggests that Yūjirō consistently “stood in for [a] more active masculinity, one that could stand up to foreign men.” Deborah Shamoon (2002, 6) writes that

“Shintaro’s GI style haircut became known as the ‘Shintaro cut’, and especially after Yūjirō appeared in the movies sporting the same style, it became extremely popular (Harada 38). In fact, fans eagerly imitated everything about Yūjirō, from his Hawaiian shirts and ‘mambo pants’ to his fast, clipped speech, to his swaggering gait.”

Such celebrity was fostered by the simultaneous expansion of a magazine publishing industry, which exploited the fascination with the supposedly angry and sexualised taiyōzoku youth, including through photographs that helped to consolidate Yūjirō as the image of his generation (Raine 2005).

This fascination was predictably accompanied by protest, by housewives and PTAs, against Crazed Fruit and the taiyōzoku films in general. Cuts required by Eirin, including the shortening of a shot in which Natsuhisa rips Eri’s skirt and in which her moan can be heard, retained a sexual suggestiveness that was beyond the limits of American films at the time and beyond the pale for local protesters upset at such depictions of college students. The protesters succeeded in restricting Crazed Fruit to viewers eighteen years and over in some cities, prohibiting sexually explicit public advertising, and requiring that U.S. and independent films be submitted to Eirin for classification. Despite their commercial success, and only one month following the release of Crazed Fruit, the studios announced they would no longer produce taiyōzoku films. – Liam Grealy & Catherine Driscoll

Further reading:

– Raine, M. (2005). Crazed Fruit: Imagining a new Japan – the taiyozoku films. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/373-crazed-fruit-imagining-a-new-japan-the-taiyozoku-films

– Raine, M. (2001). Ishihara Yûjirô: Youth, celebrity, and the male body in late-1950s Japan. In D. Washburn (ed.) Word and image in Japanese cinema, (pp. 202-225). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

– Shamoon, D. (2002). Sun tribe: Cultural production and popular culture in post-war Japan.

– Sharp, J. (2011). Historical dictionary of Japanese cinema. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Toronto & Plymouth.

– Standish, I. (2005). A new history of Japanese cinema: A century of narrative film. Continuum International Publishing Group, New York & London.