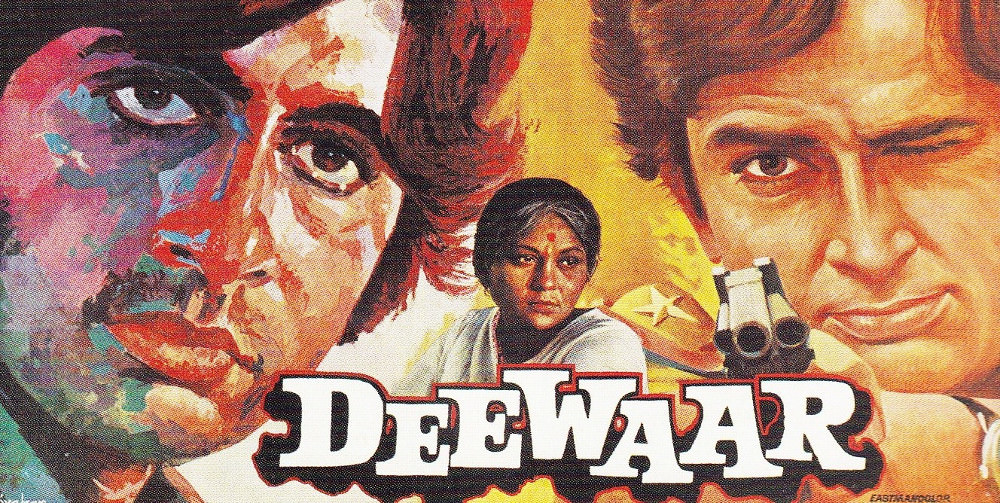

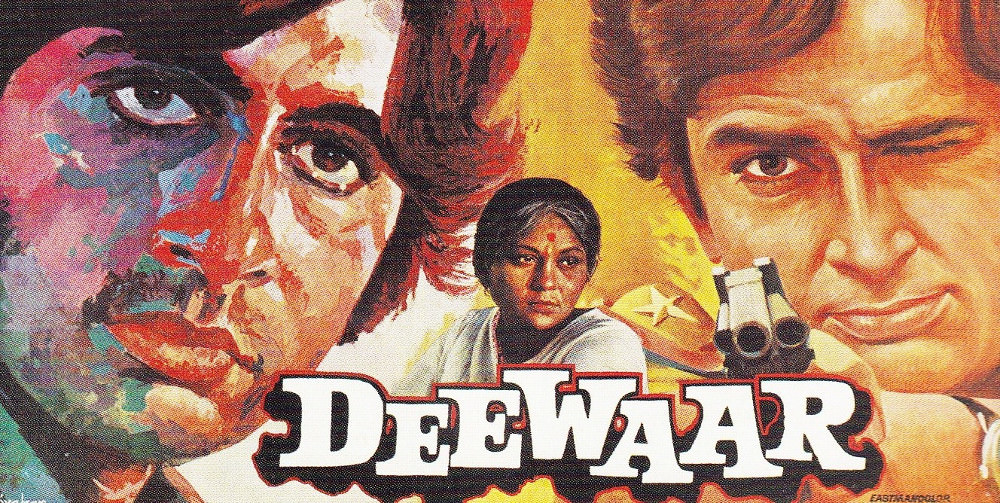

Deewaar

India

In 1975 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called a state of emergency in India under a Maintenance of Internal Security Act, citing external threats and imprisoning internal political opponents. This followed allegations of electoral malpractice against her, and the rise of the “Janata Morcha” (“People’s Front”), which was subsequently formalised as an amalgamation of parties (“Janata Party”) opposed to Gandhi’s Congress government and led by Jayaprakesh Narayan. On 12 June Gandhi was found guilty and barred from public office in Uttar Pradesh v. Raj. Narain, and a famous rally followed on 25 June that called for civil disobedience and the resignation of the government. The repressive state of emergency lasted until 1977 at which point the Janata Party successfully contested the election. Deewaar (The Wall, 1975), which Jyotika Virdi (1993, 26) suggests “can simultaneously be read as a family melodrama, an action-thriller, a religious-mythical or radical-subversive text”, was released into and clearly reflects this context.

Directed by Yash Chopra and starring Shashi Kapoor and Amitabh Bachchan, Deewaar draws obvious allegorical parallels with the politics of the Emergency period. It also recalls the storyline of the renowned 1957 epic Mother India (directed by Mehboob Khan and starring Nargis), in which a hard-working and impoverished mother of two sons, one dutiful and one who turns against the law and toward violent direct action, ultimately kills the latter son (Virdi 2003). The violent crime film Deewaar is told in flashback and follows two brothers, Ravi (Kapoor) and Vijay (Bachchan), a policeman and criminal respectively. The brothers share a love for their mother Sumitra (Nirupa Roy). Once Vijay’s pregnant lover is murdered, however, he embodies Bachchan’s infamous “angry young man” persona as a vengeful vigilante, and Sumitra endorses Ravi to pursue his arrest. Destitute in Mumbai, the sons’ adoration of their mother is contrasted with their trade unionist father’s misplaced idealism, the victim of managerial extortion and workers’ anger.

In a final meeting in an underpass location central to their shared childhood Vijay challenges Ravi’s values:

“These ideals, for the sake of which you’re ready to stake your life, what have they done for you? A job that pays 400-500 rupees, a rented flat, a government jeep, two sets of uniforms? Look, here I am and there you are. We both rose up from this sidewalk, but today where are you and where have I gotten to? Today I have buildings, property, a bank balance, a fine home, a car! What do you have?”

Ravi’s concise reply – “I’ve got Mum” – reflects Sumitra’s rejection of Vijay once she has discovered his lawlessness, but it is undercut by the film’s conclusion where it is clear that Vijay is his mother’s favourite son, and he dies in her arms. Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willeman (1999, 423) suggest that “although the audience’s sympathies are directed towards the working-class rebel [Vijay], the mother-nation [Sumitra] reluctantly sanctions the legalised persecution of her well-meaning but misguided son, an action with obvious parallels in the political situation of the time.” – Liam Grealy

Further reading:

– Rajadhyaksha, A., & Willemen, P. (1999). Encyclopaedia of Indian cinema: New revised edition. Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers.

– Virdi, J. (1993). Deewar: The “fiction of film and “fact” of politics. Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media(38), 26-32.

– Virdi, J. (2003). The Cinematic ImagiNation: Indian popular films as social history. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.