Zigomar

Japan

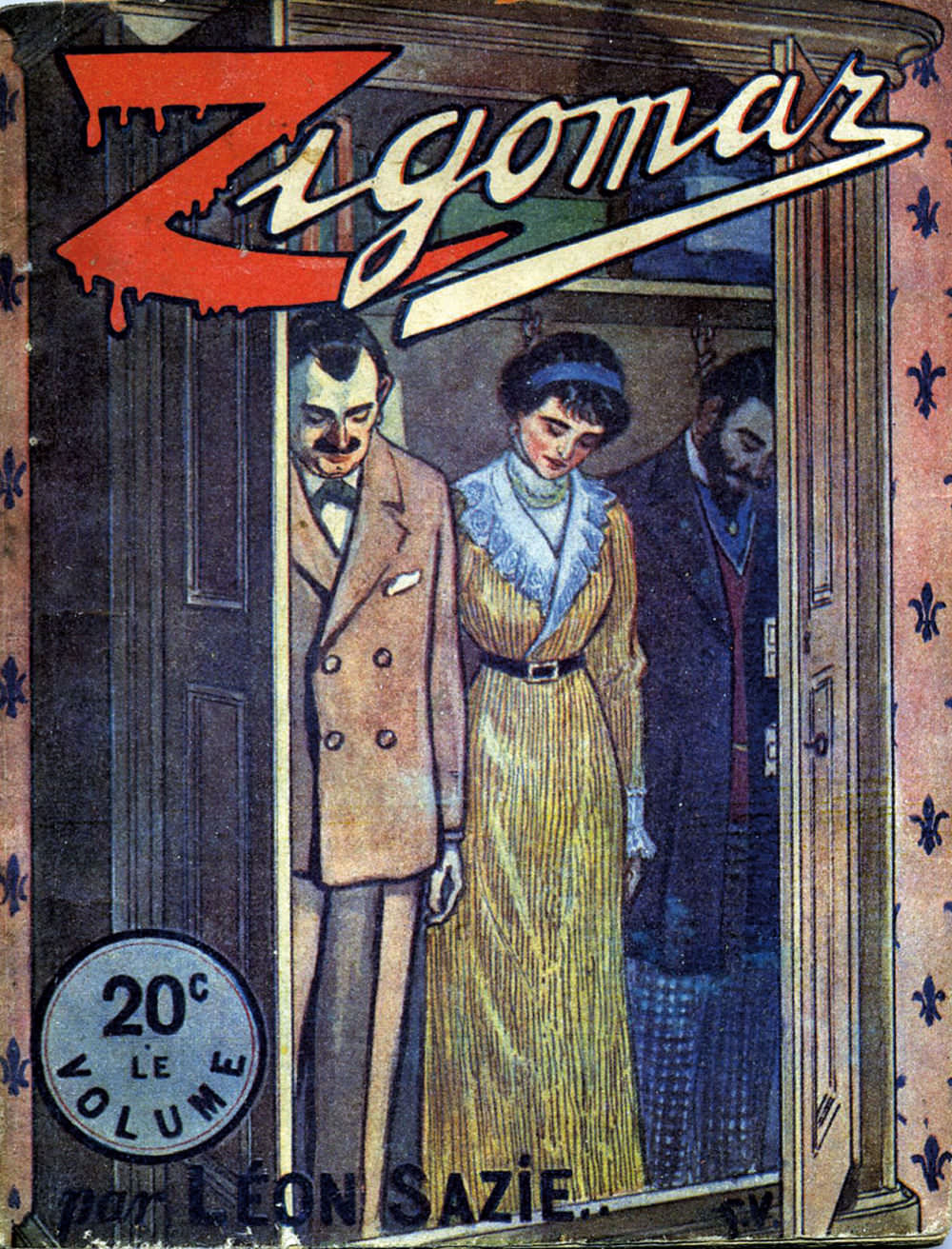

The French film Zigomar, directed by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset for the Société Française des Films Eclair, was imported into Japan in 1911, opening in the Asakusa district in November and leading to an array of locally produced sequel films and novels (see Gerow 2010, 54). These texts track Zigomar, ‘a debonair criminal mastermind and master of disguise’ (Gerow 2010, 52), as he attempts to outsmart various detectives across Europe and the Middle East. Following the release of the initial film and as others began to be exhibited, the Tokyo Asahi Shinbun ran two series of articles in 1912 on the dangers to children of motion pictures, and Zigomar specifically, suggesting the film had contributed to a spate of copycat crimes by delinquent boys (Hase 1998, 89-90). Criticisms of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police in these articles led to the police banning Zigomar films from October 1912, with other locations following.

Limited guidelines for the regulation of film existed prior to Zigomar’s importation (Mamoru 2001, 64). However, Zigomar’s success was unprecedented in Japanese cinemas, inciting consideration of school-age audiences and the effects of the moving image among the New Education Movement. While theatres’ material conditions were assumed to encourage certain unsavoury relationships with filmic texts, audiences of crime and action films were also presumed predisposed to influence and of questionable morals. Press condemnation claimed ‘those “sucked into this Zigomar” were “like ants swarming around a piece of sweet sugar”’ (in Gerow 2010, 58). With little empirical evidence, movie audiences were presumed to be dominated by young children, exacerbating these concerns about media effects and evident in this quote from the Asahi Shinbun:

“With these scenes and props, the film first leads the audience into a field of realistic impressions and there shows, putting into motion, various evil deeds. Even adult audiences with good sense and judgement are so impressed they call it ‘an interesting novelty that works well.’ The film naturally offers even more intense excitement in the minds of the young who like both adventure and strong individuals, and who idealize the winner in any situation”

(7 October 1912 in Gerow 2010).

This quote suggests concern was not simply about audiences stratified by age but about levels of understanding and knowledge that a heterogeneous audience would bring to the cinema, itself an object of unique concern. This is demonstrated, Aaron Gerow (2010, 61) suggests, by the fact that while Zigomar films were banned, no Zigomar-influenced novels were removed from bookstores.

The Zigomar controversy led to the emergence of an important precedent for Japan’s post-WWII classification system. In 1917 the Tokyo Moving Picture Regulations were released, including an “A/B” rating system. This is actually the first comprehensive film censorship code, emerging from three important studies that followed the Zigomar controversy, by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, the Imperial Education Association, and the academic Gonda Yasunosuke (Gerow 2010, 181). – Liam Grealy

Further reading:

– Gerow, A. (2010). Visions of Japanese modernity: Articulations of cinema, nation, and spectatorship, 1895-1925. University of California Press: Los Angeles.

– Hase, M. (1998). Cinemaphobia in Taishô Japan: Zigomar, delinquent boys and somnambulism. Iconics. 4: 87-100.

– Mamoru, M. (2001). On the conditions of film censorship in Japan before its systematisation. In A. Gerow & A.B. Nornes (eds) In praise of film studies: Essays in honour of Makino Mamoru, (pp. 46-67). Kinema Club: Yokohama & Ann Arbor.