Awarded Abroad and Banned in China: The Blue Kite

China

Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang, The Blue Kite (1993, Lán fēngzheng) is one of a number of mainland Chinese films from the early 1990s that received accolades from international film festivals while subject to domestic controversy. Tian is typically grouped among China’s so-called “Fifth Generation” filmmakers, including Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou, and other graduates of the first class of the Beijing Film Academy once it was reopened following the Cultural Revolution. Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993), a melodrama depicting the relationship between two male stars in a mid-20th century Peking opera, was released in China in July 1993, but subsequently removed from theatres and banned by August. This treatment of the 1993 Palme d’Or winner provoked international condemnation and in September a censored version was allowed to return to local screens by a sensitive Chinese government in the midst of a bid to host the 2000 Summer Olympic Games. Yimou’s portrayal of Chinese life from the 1940s to the 1970s in To Live (1994) was also banned in China, while it received the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, among other awards. Tian’s The Blue Kite was similarly banned in mainland China, while receiving the Grand Prize at the Tokyo International Film Festival, among other international accolades. While Tian had worked in the state-owned Beijing Film Studio during The Blue Kite’s production, and the film had been pre-approved by the Central Film Bureau (then under the Ministry of Culture), his film showed insufficient fidelity to the original script such that the studio would not submit his footage to the Central Film Bureau for approval for post-production (Clements 1994; Chute 1994). Tian exported his footage without permission to Japan for post-production and public screening, which resulted in the government imposing a ten-year filmmaking ban on the director.

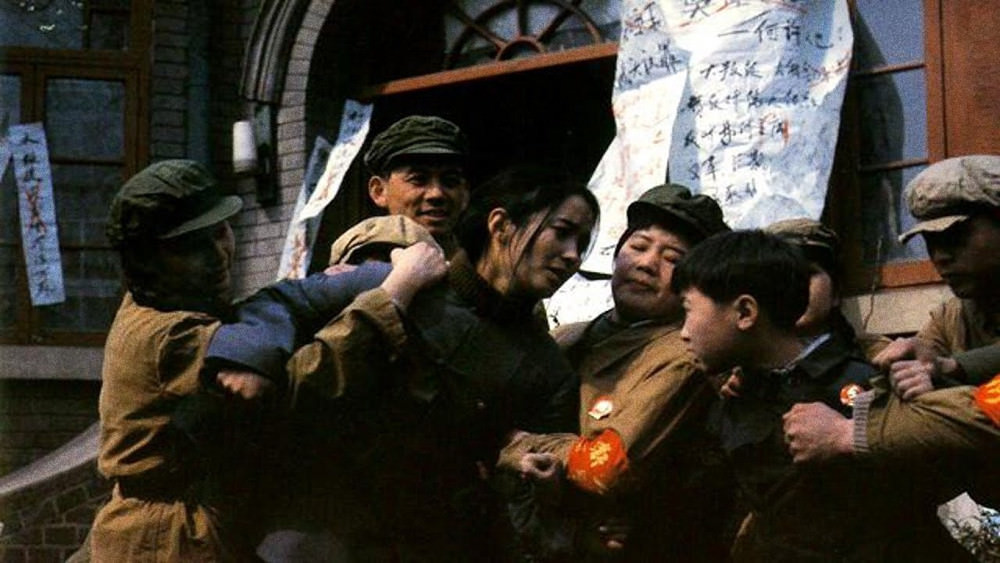

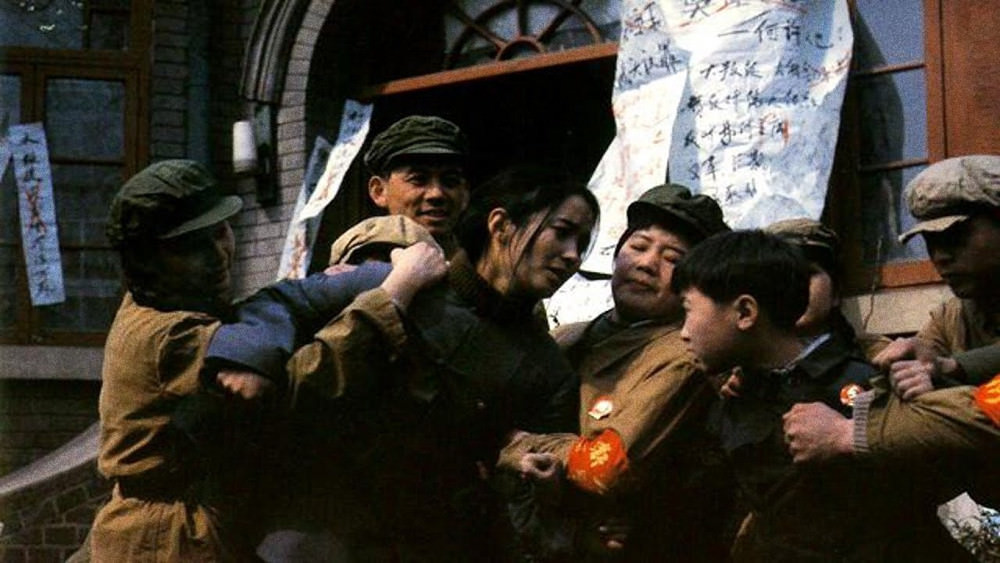

The Blue Kite is centred on a boy, Tietou (“Iron head”) and the domestic life of his changing family, beginning on Dry Well Lane in Beijing. The action takes place between 1953 and 1968, which captures a number of important periods in Chinese history, including the Hundred Flowers Campaign (1956-1957), the Great Leap Forward (1958-1962), and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). In this way, Zhang Xudong (2003, 624) describes The Blue Kite as “a visual reconstruction of the national memory through a post-revolutionary catharsis of trauma.” Under the Hundred Flowers Campaign, the ruling Communist Party encouraged citizens to openly express their opinions of the regime, which subsequently condemned many of those citizens to re-education camps and death during the anti-rightist campaign that followed from 1957 to 1959. The Great Leap Forward was a Communist Party of China campaign to consolidate a socialist system through industrialisation and collectivisation, in particular in agricultural production, but which resulted in the Great Chinese famine. The Cultural Revolution was launched in 1966 with further purges of state enemies accused of promoting bourgeois ideology. Throughout The Blue Kite, such state-led policies are represented through the co-option of citizens into the mundane violences required for their success, such as accusation and denouncement. Drawing on melodramatic conventions to depict history on an almost epic scale, The Blue Kite represents the effects of state machinations at the level of the family and everyday life, most obviously through Tietou’s three father figures. Tietou’s biological father, Shalong (Pu Quanxin), is a librarian who is denounced as a rightist by his colleagues following the Hundred Flowers Campaign, and who dies in an accident at a labour camp. Following a period of severe poverty, Tietou’s mother Shujuan (Lu Liping) marries Shalong’s former friend, Guadong, but he dies shortly thereafter from liver failure and malnutrition brought on by a period at a labour camp. In the final chapter, “Step-father”, Shujuan marries a third husband, Lu Wei. A minor party official, Lu is denounced by fellow party members for counterrevolutionary actions. Tietou attacks a party official in the mob that has appeared to take his step-father away for trial and in response he is beaten, with the film concluding with Tietou bleeding on the pavement. – Liam Grealy

Further reading:

– Chute, D. (1994). Beyond the law. Film Comment. 30 January, 60.

– Clements, M. (1994). Film, “The Blue Kite” sails beyond censors. The New York Times. 3 April.

– Zhang, X. (2003). National trauma, global allegory: Reconstruction of collective memory in Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The blue kite. Journal of Contemporary China. 12(37): 623-638.